A special case needs to be made for James Whale. Though not exactly forgotten—a pair of genre-defining horror masterpieces (Frankenstein and The Invisible Man) and two satires (The Old Dark House and Bride of Frankenstein) have kept him in circulation—he is certainly misremembered. Instead of the easily definable horror-auteur that history would prefer, Whale was an artist of many mediums (theater, cinema, painting, drawing), genres and sensibilities, but the unavailability of the majority of his body of work, either in theatrical revivals or on home video, has prevented audiences from fully understanding him. Encompassing the full range of Whale's style, from gothic to modern and screwball to macabre, Film Forum's 16-film retrospective will do much to restore the director's lopsided legacy.

A special case needs to be made for James Whale. Though not exactly forgotten—a pair of genre-defining horror masterpieces (Frankenstein and The Invisible Man) and two satires (The Old Dark House and Bride of Frankenstein) have kept him in circulation—he is certainly misremembered. Instead of the easily definable horror-auteur that history would prefer, Whale was an artist of many mediums (theater, cinema, painting, drawing), genres and sensibilities, but the unavailability of the majority of his body of work, either in theatrical revivals or on home video, has prevented audiences from fully understanding him. Encompassing the full range of Whale's style, from gothic to modern and screwball to macabre, Film Forum's 16-film retrospective will do much to restore the director's lopsided legacy.Wednesday, December 09, 2009

James Whale at Film Forum

A special case needs to be made for James Whale. Though not exactly forgotten—a pair of genre-defining horror masterpieces (Frankenstein and The Invisible Man) and two satires (The Old Dark House and Bride of Frankenstein) have kept him in circulation—he is certainly misremembered. Instead of the easily definable horror-auteur that history would prefer, Whale was an artist of many mediums (theater, cinema, painting, drawing), genres and sensibilities, but the unavailability of the majority of his body of work, either in theatrical revivals or on home video, has prevented audiences from fully understanding him. Encompassing the full range of Whale's style, from gothic to modern and screwball to macabre, Film Forum's 16-film retrospective will do much to restore the director's lopsided legacy.

A special case needs to be made for James Whale. Though not exactly forgotten—a pair of genre-defining horror masterpieces (Frankenstein and The Invisible Man) and two satires (The Old Dark House and Bride of Frankenstein) have kept him in circulation—he is certainly misremembered. Instead of the easily definable horror-auteur that history would prefer, Whale was an artist of many mediums (theater, cinema, painting, drawing), genres and sensibilities, but the unavailability of the majority of his body of work, either in theatrical revivals or on home video, has prevented audiences from fully understanding him. Encompassing the full range of Whale's style, from gothic to modern and screwball to macabre, Film Forum's 16-film retrospective will do much to restore the director's lopsided legacy.Wednesday, November 18, 2009

M. Hulot's Holiday (1953)

Simply put, Jacques Tati's M. Hulot's Holiday (1953) is one of the most delightful cinematic experiences I have ever encountered, and it is now showing at Film Forum in a restored 35mm print. Like the film's infectious, amiable theme song—whose breezy melody fluidly passes from saxophone to guitar to vibes to piano without interrupting the phrasing—Tati, his camera and his on-screen alter-ego Hulot flit amongst the beachfront tourists like a fellow vacationer. With his perennial floppy hat and a pipe protruding from his lips, Hulot putters into town in his rustbucket and proceeds to join his compatriots in an attempt to enjoy some rest and relaxation under the sun.

Simply put, Jacques Tati's M. Hulot's Holiday (1953) is one of the most delightful cinematic experiences I have ever encountered, and it is now showing at Film Forum in a restored 35mm print. Like the film's infectious, amiable theme song—whose breezy melody fluidly passes from saxophone to guitar to vibes to piano without interrupting the phrasing—Tati, his camera and his on-screen alter-ego Hulot flit amongst the beachfront tourists like a fellow vacationer. With his perennial floppy hat and a pipe protruding from his lips, Hulot putters into town in his rustbucket and proceeds to join his compatriots in an attempt to enjoy some rest and relaxation under the sun.Read my full review of M. Hulot's Holiday here at The L Magazine.

Friday, November 13, 2009

Migrating Forms' Half-Inch Half-Life: "Tracy the Outlaw" (1928)

This past summer, I was invited to participate in Migrating Forms' Half-Inch Half-Life, self-described as "a semi-intimate, public viewing room showcasing a 43-hour marathon of selections from the personal VHS archives of artists, critics, curators, scholars and other devotees to the medium, on a large, media-appropriate television set." My contribution was a rare VHS tape of Tracy the Outlaw. Below are my program notes which accompanied the exhibition.

This past summer, I was invited to participate in Migrating Forms' Half-Inch Half-Life, self-described as "a semi-intimate, public viewing room showcasing a 43-hour marathon of selections from the personal VHS archives of artists, critics, curators, scholars and other devotees to the medium, on a large, media-appropriate television set." My contribution was a rare VHS tape of Tracy the Outlaw. Below are my program notes which accompanied the exhibition.Tracy the Outlaw is a silent Western from 1928. An independent production by Foto Art Productions, it doesn’t look like most movies we remember from that same year – it neither has the artistic touches of Victor Sjostrom’s The Wind, the stylizations of The Docks of New York, or any of the technical or narrative proficiency that was the Hollywood standard by that time. And that’s exactly why Tracy the Outlaw is important: Hollywood isn’t everything, and outside of it were independent producers and distributors, making raw, unkempt, flawed, and wonderful movies.

But lacking stars, polish, prestige, and any sort of critical status, Tracy the Outlaw isn’t likely to make any appearances at revival houses, or even in history books. It’s a miracle that it was even brought to VHS (and in a pretty decent print) by Videobrary, one of many companies during the 1980s-1990s who specialized in overlooked niches of early cinema, including B-Westerns. There was also Sinister Cinema, Hollywood’s Attic, Nostalgia Family, and Grapevine, to name just a few. (The last two are still around, releasing material on DVD.) There was something special about those small VHS distributors – some sort of magic that seems to be lost in the age of internet. When I was 12, I ordered a video from Facets in Chicago, and suddenly I began receiving black-and-white photocopied catalogs and typewritten lists of old movies on VHS. They were coming from small towns in Maine like Thomaston. I have no clue how I got on this mailing list circuit, but I was flooded with titles I had never heard about. Sadly, I never kept them, as I’d love to see all the great movies I passed up on because of lack of access/information.

But now many of those companies are gone. I no longer receive those wonderful lists. Once in a while, I come across a trove of old Grapevine releases, or some other company. That’s how I found Tracy the Outlaw – three dollars, stuck on a shelf between such other potential gems as Ghost Patrol (a sci-fi Western from 1936) and Border Romance (a musical Western about fugitives from 1929) (both films were released by Sinister Cinema, by the way). The audience for these films was probably small when they came out, and it’s only dwindled in the passing decades. No major home video distributor would ever take these on – the chance of making a profit would be slim. That’s why Grapevine, Videobrary, and all those other companies were – and continue to be – so vital.

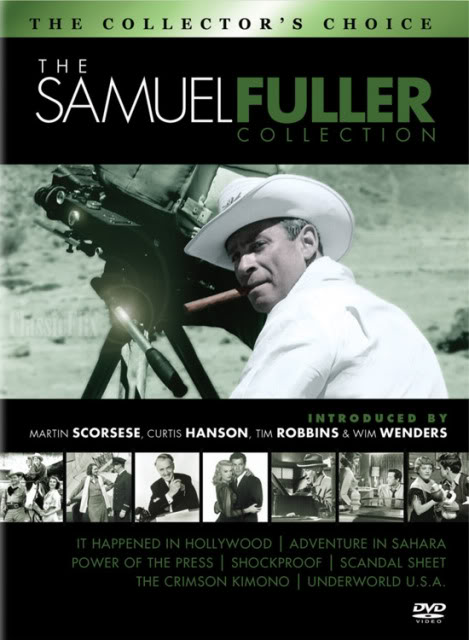

The Samuel Fuller Collection

Samuel Fuller's movies are equal parts street corner and gutter, a combination of two-inch-headline journalistic hullabaloo and pulp poetics. Andrew Sarris called him "an authentic American primitive," while Dana Polan described him as "the opposite of graceful; his style seems to suggest that in a world where grace provides little redemption, its utilization would be a kind of lie." This one-of-a-kind, immediately recognizable persona is on full display in Sony's seven disc box set The Samuel Fuller Collection, which pulls together seven hard-to-find films that the cigar-chomping filmmaker was involved in, none of which were previously available on DVD...

Samuel Fuller's movies are equal parts street corner and gutter, a combination of two-inch-headline journalistic hullabaloo and pulp poetics. Andrew Sarris called him "an authentic American primitive," while Dana Polan described him as "the opposite of graceful; his style seems to suggest that in a world where grace provides little redemption, its utilization would be a kind of lie." This one-of-a-kind, immediately recognizable persona is on full display in Sony's seven disc box set The Samuel Fuller Collection, which pulls together seven hard-to-find films that the cigar-chomping filmmaker was involved in, none of which were previously available on DVD...Read my full review of The Samuel Fuller Collection here at The L Magazine.

Friday, November 06, 2009

Death In the Garden (1956)

A drifter, a prostitute, a priest, a miner, and his deaf-mute daughter walk into a South American jungle. It sounds like the start of a joke, but it happens to be the set-up for Luis Buñuel's anti-colonialist adventure-satire Death in the Garden (1956), just out on DVD from Microcinema International. When Chark (Georges Marchal, of Buñuel's Belle de Jour and The Milky Way) stumbles through a town square past a firing squad, he finds himself in the midst of a revolution.

A drifter, a prostitute, a priest, a miner, and his deaf-mute daughter walk into a South American jungle. It sounds like the start of a joke, but it happens to be the set-up for Luis Buñuel's anti-colonialist adventure-satire Death in the Garden (1956), just out on DVD from Microcinema International. When Chark (Georges Marchal, of Buñuel's Belle de Jour and The Milky Way) stumbles through a town square past a firing squad, he finds himself in the midst of a revolution.Read my full review of Death in the Garden here at The L Magazine.

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

Interview with Vagabond, director of "Machetero"

Machetero, which screens this Thursday, Oct. 29 at the New York International Independent Film and Video Festival, is a film whose guerrilla production matches both the film's visual aesthetic and its narrative. It tells two stories concurrently: one in which imprisoned revolutionary Pedro Taino (Not4Prophet) is interviewed by a journalist (Jarmush regular Isaach De Bankolé, pictured), and the other about the political awakening of a young man (Kelvin Fernandez) on the streets of New York. As directed and written by Vagabond, Machetero's radical politics extend to the film's non-linear narrative, and its use of on-screen titles, foregrounding the revolutionary literature passed amongst the characters, as well as lyrics from the soundtrack by the NYC-based band Ricanstruction (of which Not4Prophet is the lead singer). Recently, I spoke to Vagabond about the film's intersections of art and politics.

Machetero, which screens this Thursday, Oct. 29 at the New York International Independent Film and Video Festival, is a film whose guerrilla production matches both the film's visual aesthetic and its narrative. It tells two stories concurrently: one in which imprisoned revolutionary Pedro Taino (Not4Prophet) is interviewed by a journalist (Jarmush regular Isaach De Bankolé, pictured), and the other about the political awakening of a young man (Kelvin Fernandez) on the streets of New York. As directed and written by Vagabond, Machetero's radical politics extend to the film's non-linear narrative, and its use of on-screen titles, foregrounding the revolutionary literature passed amongst the characters, as well as lyrics from the soundtrack by the NYC-based band Ricanstruction (of which Not4Prophet is the lead singer). Recently, I spoke to Vagabond about the film's intersections of art and politics. Could you say a little about the word "Machetero," where it comes from, and why you chose it as your title?

The direct Spanish translation of the word "machetero" is someone who works with a machete. However, there is a cultural definition to the word that is unique to Puerto Rico. The "Macheteros" were sugarcane field workers who fought against Spanish colonial rule, and when the US invaded Puerto Rico in 1898 during the Spanish-American war, they fought against the Americans as well. In the late 1960s, Puerto Rican independence leader Filiberto Ojeda Rios started a clandestine armed organization called "Ejercito Popular Boricua" ("Popular Puerto Rican Army"). Puerto Ricans throughout the Diaspora called them "Macheteros".

The title of the film comes from a saying the Macheteros had, "¡Todo Boricua Machetero!" ("All Puerto Ricans Are Machetero!") which connected Puerto Ricans to their revolutionary past. When I thought more about that saying, it seemed to me that what the EPB was trying to do was to create this idea of the Machetero as warrior and protector of the Puerto Rican people in much the same way that the Samurai is in Japan.

Thursday, October 22, 2009

Black Rain (1989)

It seems grossly obvious to lump adjectives like "haunting" and "harrowing" onto Imamura's narrative about Hiroshima survivors dealing with bodily and psychological strain in the aftermath, particularly when the film is most affecting when it is least direct. The opening sequence of the bomb dropping is undeniably powerful, but the simple shot of black rain landing on a young girl's face is even more so. Restraining even reticence, Imamura cuts the shot short, limiting the possibility of catharsis through the symbolic image. What is shown on the surface is never so important as what is not, Imamura suggests throughout the movie, and that the most devastating wounds are those beyond visibility...

It seems grossly obvious to lump adjectives like "haunting" and "harrowing" onto Imamura's narrative about Hiroshima survivors dealing with bodily and psychological strain in the aftermath, particularly when the film is most affecting when it is least direct. The opening sequence of the bomb dropping is undeniably powerful, but the simple shot of black rain landing on a young girl's face is even more so. Restraining even reticence, Imamura cuts the shot short, limiting the possibility of catharsis through the symbolic image. What is shown on the surface is never so important as what is not, Imamura suggests throughout the movie, and that the most devastating wounds are those beyond visibility...Read my full review of Black Rain here at The L Magazine.

Monday, October 19, 2009

Daniel and Abraham (2009)

Typically, when we speak of film as a collaborative art form we mean that the production process involves so many people (be it dozens or hundreds) that, at some level, assigning individual credit is insufficient and misleading. No one element in a completed film exists on its own: always it is interacting with other sights, sounds, and processes. Daniel and Abraham takes this notion of collaboration to an ambitious, minimalist extreme. The entire crew of this feature film consists of three people: director Ryan Eslinger, and the film’s sole actors David Williams and Gary Lamadore. All three shared writing duties, as well as all the other behind-the-scenes responsibilities. However, this stripped-down, DIY production style makes for more than just an interesting back-story to relate in interviews and post-screening Q&As. Instead, it’s an ironic counterpoint to the film’s narrative of deep-seated mistrust and human disconnection. The intense participation and investment of the makers comes through loud and clear on-screen.

Typically, when we speak of film as a collaborative art form we mean that the production process involves so many people (be it dozens or hundreds) that, at some level, assigning individual credit is insufficient and misleading. No one element in a completed film exists on its own: always it is interacting with other sights, sounds, and processes. Daniel and Abraham takes this notion of collaboration to an ambitious, minimalist extreme. The entire crew of this feature film consists of three people: director Ryan Eslinger, and the film’s sole actors David Williams and Gary Lamadore. All three shared writing duties, as well as all the other behind-the-scenes responsibilities. However, this stripped-down, DIY production style makes for more than just an interesting back-story to relate in interviews and post-screening Q&As. Instead, it’s an ironic counterpoint to the film’s narrative of deep-seated mistrust and human disconnection. The intense participation and investment of the makers comes through loud and clear on-screen.Read my full review of Daniel and Abraham here at Hammer to Nail.

Friday, October 16, 2009

Interview with Charles Silver

Last month, the Museum of Modern Art embarked on one of its most ambitious and exciting film series in recent years, An Auteurist History of Film. Curated by Charles Silver, the two-year-plus series takes as its organizational principle the Auteur Theory (which posits the director as the primary author of a film), and aims to cover pre-cinema (such as “magic lanterns” and other early visual and photographic technologies) all the way to the present day. The breadth of its programming is highly promising, with opportunities to revisit and reevaluate more canonical works, as well the chance to see long-neglected and often non-commercially available films (such as Benjamin Christensen’s The Mysterious X from 1914). Recently, I had the pleasure of speaking with Charles Silver about the guiding principles of his latest series, as well changes in the New York City film scene over the past several decades.

Last month, the Museum of Modern Art embarked on one of its most ambitious and exciting film series in recent years, An Auteurist History of Film. Curated by Charles Silver, the two-year-plus series takes as its organizational principle the Auteur Theory (which posits the director as the primary author of a film), and aims to cover pre-cinema (such as “magic lanterns” and other early visual and photographic technologies) all the way to the present day. The breadth of its programming is highly promising, with opportunities to revisit and reevaluate more canonical works, as well the chance to see long-neglected and often non-commercially available films (such as Benjamin Christensen’s The Mysterious X from 1914). Recently, I had the pleasure of speaking with Charles Silver about the guiding principles of his latest series, as well changes in the New York City film scene over the past several decades.The L Magazine: What was the motivation for doing this series now?

Charles Silver: It seems like as good a time as any. I’ve been at The Museum of Modern Art for almost 39 years now, and I’ve been going to the movies for close to 60 (or maybe more) and I thought it would be good to go back and survey our film archive (which begins in the 1890s and goes up to the present day) and try to define the Auteur theory through the collection. There have been, in the past, other film history cycles at the museum, so it is not totally novel, but I thought that approaching it from the Auteur Theory would make the most coherent expression of film history, at least up until the point that the studios broke down, and we had films really by committees and computers. It is hard to argue that a lot of current movies could be the expression of individual artists although I think there are many exceptions.

Read my full interview with Charles Silver at The L Magazine.

Mother (2009)

Bong Joon-ho’s films have been characterized by bizarre humor (Barking Dogs Don’t Bite) tinged with dark political commentary (Memories of Murder) in the guise of cross-genre experiments (The Host). Bong’s fourth feature, Mother, continues this trend, and while its examination of (in)justice bears certainly similarities to his second movie, Memories of Murder, it is by no means a repetition. As his latest film shows, Bong able to hit all the notes that audiences have come to expect in his movies while still developing his narrative techniques and visual aesthetic.

Bong Joon-ho’s films have been characterized by bizarre humor (Barking Dogs Don’t Bite) tinged with dark political commentary (Memories of Murder) in the guise of cross-genre experiments (The Host). Bong’s fourth feature, Mother, continues this trend, and while its examination of (in)justice bears certainly similarities to his second movie, Memories of Murder, it is by no means a repetition. As his latest film shows, Bong able to hit all the notes that audiences have come to expect in his movies while still developing his narrative techniques and visual aesthetic.Read my full review of Mother here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

Marlene (1984)

Marlene is not your typical non-fiction celebrity portrait—and really, how could it be when your "star" refuses to appear on-camera? Dietrich herself admits that "Documentary is a thing that connects the voices that are talking," so what happens when that seemingly crucial connection is severed? Schell uses this disjunction between sound and image to explore the star persona of "Diectrich" to see what, if anything, it reveals of the "real" Dietrich that she so desperately tried to hide from the camera.

Marlene is not your typical non-fiction celebrity portrait—and really, how could it be when your "star" refuses to appear on-camera? Dietrich herself admits that "Documentary is a thing that connects the voices that are talking," so what happens when that seemingly crucial connection is severed? Schell uses this disjunction between sound and image to explore the star persona of "Diectrich" to see what, if anything, it reveals of the "real" Dietrich that she so desperately tried to hide from the camera.Read my full review of Marlene here at The L Magazine.

Wednesday, October 07, 2009

Crossroads of Youth (1934)

Viewing Crossroads of Youth in its intended presentation format, the way Korean audiences would have when it originally premiered in 1934, was like encountering an entirely different art form. All that I thought I knew about how to watch silent cinema—forgiving improper frame rates that make the actors’ movement cartoonish, or understanding that live accompaniment may have differed not only from theater to theater, but from performance to performance at the same venue—was not sufficient to prepare me for how to take in the wide array of sights and sounds—yes, sounds—of this special New York Film Festival screening.

Viewing Crossroads of Youth in its intended presentation format, the way Korean audiences would have when it originally premiered in 1934, was like encountering an entirely different art form. All that I thought I knew about how to watch silent cinema—forgiving improper frame rates that make the actors’ movement cartoonish, or understanding that live accompaniment may have differed not only from theater to theater, but from performance to performance at the same venue—was not sufficient to prepare me for how to take in the wide array of sights and sounds—yes, sounds—of this special New York Film Festival screening.Read my full review of Crossroads of Youth here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

Munyurangabo (2007)

I first saw Lee Isaac Chung's Munyurangabo (2007) at New Directors/New Films in 2008, and was struck both by the film's reticent morality as well as by Chung's subtle yet perceptive direction. Considering its political context (the cultural memory of genocide in Rwanda), the film could have easily flown off in the direction of heavy-handed earnestness. Instead, Chung managed to reign in "the message" and focus more on a narrative that is hauntingly empathetic in its exploration of cultural clashes, without giving in to easy answers or reductive symbolism. For the work of first-time filmmaker working with non-professional actors and improvising scenes based on a brief scenario in a language he doesn't speak, it's extremely impressive that Munyurangabo is as nuanced and discerning as it is, in both its political content and cinematic sensibility.

I first saw Lee Isaac Chung's Munyurangabo (2007) at New Directors/New Films in 2008, and was struck both by the film's reticent morality as well as by Chung's subtle yet perceptive direction. Considering its political context (the cultural memory of genocide in Rwanda), the film could have easily flown off in the direction of heavy-handed earnestness. Instead, Chung managed to reign in "the message" and focus more on a narrative that is hauntingly empathetic in its exploration of cultural clashes, without giving in to easy answers or reductive symbolism. For the work of first-time filmmaker working with non-professional actors and improvising scenes based on a brief scenario in a language he doesn't speak, it's extremely impressive that Munyurangabo is as nuanced and discerning as it is, in both its political content and cinematic sensibility.Read my full review of Munyurangabo here at The L Magazine.

Tuesday, October 06, 2009

The Fall of the House of Usher (1928)

Literary adaptations for the silent screen pose certain difficulties. Limited to intertitles and images, how then to cinematically “translate” text-based literature onto the screen without turning the movie into an illustrated manuscript? For an author like Edgar Allan Poe, there is the issue of not only plot, but also the cadence of his language, which gives so much flavor and atmosphere to the stories. For his film of The Fall of the House of Usher, Jean Epstein took a bold approach, not so much following Poe’s directly as moving parallel to it, using cinema’s distinct capabilities to create something analogous to what Poe was doing with language. As Jean-André Fieschi wrote of Epstein, “he is less interested in the expressive possibilities of visual writing than in a certain degree of autonomy pertaining to it.”

Literary adaptations for the silent screen pose certain difficulties. Limited to intertitles and images, how then to cinematically “translate” text-based literature onto the screen without turning the movie into an illustrated manuscript? For an author like Edgar Allan Poe, there is the issue of not only plot, but also the cadence of his language, which gives so much flavor and atmosphere to the stories. For his film of The Fall of the House of Usher, Jean Epstein took a bold approach, not so much following Poe’s directly as moving parallel to it, using cinema’s distinct capabilities to create something analogous to what Poe was doing with language. As Jean-André Fieschi wrote of Epstein, “he is less interested in the expressive possibilities of visual writing than in a certain degree of autonomy pertaining to it.”Read my full review of The Fall of the House of Usher here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

Saturday, October 03, 2009

Wild Grass (2009)

The ever-playful Resnais continually reinvents his movie throughout the story’s progression (quite literally up until the last frame, with a truly bizarre final shot!) with red herrings, plot reversals, false endings, and other sudden tonal shifts. At age 87, and with over sixty years of directing behind him, Resnais is still one step ahead of the audience, and his filmmaking remains as vigorous and youthful as ever.

The ever-playful Resnais continually reinvents his movie throughout the story’s progression (quite literally up until the last frame, with a truly bizarre final shot!) with red herrings, plot reversals, false endings, and other sudden tonal shifts. At age 87, and with over sixty years of directing behind him, Resnais is still one step ahead of the audience, and his filmmaking remains as vigorous and youthful as ever.Read my full review of Wild Grass here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

Thursday, October 01, 2009

Police, Adjective (2009)

One of the great ironies of the detective-centered plot is that, more often than not, it is the observer who is being observed. And not just by other characters in the narrative, but primarily by us, whether we are watching a movie or television show, or reading a pulp yarn. From the Continental Op to Veronica Mars, it has been the detectives themselves more than their cases that have commanded our attention. It is this attraction that is under scrutiny in Corneliu Porumboiu’s Police, Adjective, a movie that bends, as much as it obeys, the genre’s conventions.

One of the great ironies of the detective-centered plot is that, more often than not, it is the observer who is being observed. And not just by other characters in the narrative, but primarily by us, whether we are watching a movie or television show, or reading a pulp yarn. From the Continental Op to Veronica Mars, it has been the detectives themselves more than their cases that have commanded our attention. It is this attraction that is under scrutiny in Corneliu Porumboiu’s Police, Adjective, a movie that bends, as much as it obeys, the genre’s conventions.Read my full review of Police, Adjective here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

Daughter of Darkness (1948) and Burke and Hare (1972)

UK-based distributor Salvation Films have just unveiled two new-to-DVD releases on their Redemption USA line: Daughter of Darkness> (1948) and Burke and Hare (1972). While both share a debt to Val Lewton's less-is-more B-horror productions (the former to Cat People [1942] and the latter to The Body Snatcher [1945]), neither is merely imitative. Instead, they diverge from their forerunners in distinctive, and often eccentric, ways, culminating in works that at once pay tribute to their roots but also stand apart.

UK-based distributor Salvation Films have just unveiled two new-to-DVD releases on their Redemption USA line: Daughter of Darkness> (1948) and Burke and Hare (1972). While both share a debt to Val Lewton's less-is-more B-horror productions (the former to Cat People [1942] and the latter to The Body Snatcher [1945]), neither is merely imitative. Instead, they diverge from their forerunners in distinctive, and often eccentric, ways, culminating in works that at once pay tribute to their roots but also stand apart.Read my full reviews here at The L Magazine.

Monday, September 28, 2009

Sweetgrass (2009)

Is Sweetgrass even a movie about sheep? Not in the sense that March of the Penguins is about penguins. There’s hardly a frame in Sweetgrass without a specimen of Ovis aries bleating, grazing, or even gazing into the camera, yet the educational and didactic rhetoric that typically characterizes entries in the “animal documentary” genre is noticeably absent. Diverging from the cutesy aesthetics that made Luc Jacquet’s penguin exposé an accessible, international hit, filmmakers Ilisa Barbash and Lucien Castaing-Taylor taken a far more empirical approach. There is no voice-over narration or “talking head” commentary, and until the very end of the movie there are no explanatory intertitles, either. Instead, they have crafted an ambient narrative in the cinéma vérité tradition that demands patient observation from the audience, but also rewards their attentiveness...

Is Sweetgrass even a movie about sheep? Not in the sense that March of the Penguins is about penguins. There’s hardly a frame in Sweetgrass without a specimen of Ovis aries bleating, grazing, or even gazing into the camera, yet the educational and didactic rhetoric that typically characterizes entries in the “animal documentary” genre is noticeably absent. Diverging from the cutesy aesthetics that made Luc Jacquet’s penguin exposé an accessible, international hit, filmmakers Ilisa Barbash and Lucien Castaing-Taylor taken a far more empirical approach. There is no voice-over narration or “talking head” commentary, and until the very end of the movie there are no explanatory intertitles, either. Instead, they have crafted an ambient narrative in the cinéma vérité tradition that demands patient observation from the audience, but also rewards their attentiveness...Read my full review of Sweetgrass here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

Thursday, September 24, 2009

Private Century (2006-2008)

Originally an eight-part miniseries for Czech television, Sikl's cycle recollects the history of Czechoslovakia throughout the twentieth century by using different families' home movies with narration based on memoirs, diaries, and interviews with surviving friends and family. Each episode tells a distinctive story (though a couple are related), and together they form a powerful alternative to any notion of an official history that privileges politicians and isolated demographics. Instead, the only milestones celebrated here are births, first loves, family gatherings and other minutiae that capture joys both banal and transcendent. The tragedies, however, are inexorably linked to the larger political climate, and Sikl's microcosms bring much-needed specificity to the ambiguities of history's annals.

Originally an eight-part miniseries for Czech television, Sikl's cycle recollects the history of Czechoslovakia throughout the twentieth century by using different families' home movies with narration based on memoirs, diaries, and interviews with surviving friends and family. Each episode tells a distinctive story (though a couple are related), and together they form a powerful alternative to any notion of an official history that privileges politicians and isolated demographics. Instead, the only milestones celebrated here are births, first loves, family gatherings and other minutiae that capture joys both banal and transcendent. The tragedies, however, are inexorably linked to the larger political climate, and Sikl's microcosms bring much-needed specificity to the ambiguities of history's annals.Read my full review of Private Century here at The L Magazine.

The Saragossa Manuscript (1965)

Like Russian matryoshka dolls, The Saragossa Manuscript is an incessant parade of narratives-within-narratives-within-narratives (and still more). Minor characters overtake the role of narrator, interrupting one story in order to tell their own, which is inevitably interrupted by the start of another story from another narrator. Igniting this labyrinthine progression is the chance encounter between two soldiers of opposing sides during the Napoleanic Wars, both of whom momentarily bond over a dusty, antiquated volume that, as it turns out, recollects the adventures of one of their grandfathers, Captain Alphonse van Worden. Such is the first of many leaps back and forth through time and space.

Like Russian matryoshka dolls, The Saragossa Manuscript is an incessant parade of narratives-within-narratives-within-narratives (and still more). Minor characters overtake the role of narrator, interrupting one story in order to tell their own, which is inevitably interrupted by the start of another story from another narrator. Igniting this labyrinthine progression is the chance encounter between two soldiers of opposing sides during the Napoleanic Wars, both of whom momentarily bond over a dusty, antiquated volume that, as it turns out, recollects the adventures of one of their grandfathers, Captain Alphonse van Worden. Such is the first of many leaps back and forth through time and space.Read my full review of The Saragossa Manuscript here at The L Magazine.

Paradise (2009)

Michael Almereyda’s Paradise begins with a slow tracking shot taken from a moving walkway in an airport. It’s a contradiction of movement and stasis: the camera and its holder are completely still, yet the ground beneath them perpetually propels them forward. Later in the movie, a character will comment that they love natural disasters because they “like that the earth is changing and moving.” Even the modernist architecture of the passageway—cool and steely lines converging in a distant vanishing point and whose hues fluidly shift from blue to green to purple—lends an aura of science-fiction to the shot, as though we are more than moving through a single corridor, but traveling beyond the liminal boundaries of our everyday world.

Wednesday, September 09, 2009

Foolish Wives (1922)

Foolish Wives is less a comedy than a mockery, taking as its targets the moral underpinnings of society; the sanctity of marriage; love’s purity; masculinity; femininity; and, of course, the aristocratic elite. A cursory glance at von Stroheim’s filmography reveals these as reoccurring preoccupations: compulsive concerns that the director never tired of holding a mirror up to and revealing the hypocrisy that lay beneath a virtuous façade. Von Stroheim’s laughter is sadistic. He derives pleasure from exposing the fraudulent virtues of others, even though he, more than anyone, is complicit in the widespread corruption.

Foolish Wives is less a comedy than a mockery, taking as its targets the moral underpinnings of society; the sanctity of marriage; love’s purity; masculinity; femininity; and, of course, the aristocratic elite. A cursory glance at von Stroheim’s filmography reveals these as reoccurring preoccupations: compulsive concerns that the director never tired of holding a mirror up to and revealing the hypocrisy that lay beneath a virtuous façade. Von Stroheim’s laughter is sadistic. He derives pleasure from exposing the fraudulent virtues of others, even though he, more than anyone, is complicit in the widespread corruption.Read my full review of Foolish Wives here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

Oh, the Depravity! The Cinema of Erich von Stroheim

What remains of an artist, his career, or his work, after having endured so many detours, disappointments, and derailings? Titles changed, credit revoked, productions halted, scenes reshot by other directors, and the humiliation of being thrown off the set of your own movie. These are but a smattering of the setbacks encountered by Erich von Stroheim throughout his directorial career, which began with a bang in 1919 and ended with a whimper in 1933 with a film that bore no mention of his name. All of this makes von Stroheim’s status as an auteur at once obvious and problematic. Few directors before him were as gung-ho about artistry and authorship (his name proliferates the credits of his films, leaving no question as to whom is the true creator); fewer dared to cause the scandals that he did, pushing the buttons of censors and studios past the point of compromise; and no one had their films as distorted (sometimes released incomplete) as Erich von Stroheim...

What remains of an artist, his career, or his work, after having endured so many detours, disappointments, and derailings? Titles changed, credit revoked, productions halted, scenes reshot by other directors, and the humiliation of being thrown off the set of your own movie. These are but a smattering of the setbacks encountered by Erich von Stroheim throughout his directorial career, which began with a bang in 1919 and ended with a whimper in 1933 with a film that bore no mention of his name. All of this makes von Stroheim’s status as an auteur at once obvious and problematic. Few directors before him were as gung-ho about artistry and authorship (his name proliferates the credits of his films, leaving no question as to whom is the true creator); fewer dared to cause the scandals that he did, pushing the buttons of censors and studios past the point of compromise; and no one had their films as distorted (sometimes released incomplete) as Erich von Stroheim...

Jeanne Dielman, 23, qui du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975)

A minimalist explosion of aesthetic and political rage, there's never been anything quite like Chantal Akerman's Jeanne Dielman, 23, qui du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) either before or since. At first glance the film, new on a Criterion DVD, may resemble a fusion of Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Michael Fengler's Why Does Herr R. Run Amok? (1970) and John Cassavetes' A Woman Under the Influence (1974), the former a timebomb of middle-class ennui and the latter an expression of gender-binding anxiety in the suburbs. It's true, Jeanne Dielman hits these marks, but the 25-year-old director takes these themes to a radical, transcendent extreme...

A minimalist explosion of aesthetic and political rage, there's never been anything quite like Chantal Akerman's Jeanne Dielman, 23, qui du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) either before or since. At first glance the film, new on a Criterion DVD, may resemble a fusion of Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Michael Fengler's Why Does Herr R. Run Amok? (1970) and John Cassavetes' A Woman Under the Influence (1974), the former a timebomb of middle-class ennui and the latter an expression of gender-binding anxiety in the suburbs. It's true, Jeanne Dielman hits these marks, but the 25-year-old director takes these themes to a radical, transcendent extreme...Read my full review of Jeanne Dielman, 23, qui du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles here at The L Magazine.

Gaumont Treasures: 1897-1913 (Kino)

The history of film is anything but set in stone. New discoveries, much-needed restorations and increased availability often change our perspective on topics long since thought to be behind us. The most exciting and intriguing part of Kino's new 3-DVD box set Gaumont Treasures: 1897-1913 isn't the work of either of the already celebrated filmmakers—Alice Guy (among the very first women filmmakers) or Louis Feuillade (the stylized master of series such as Les Vampires and Judex)—but a relatively obscure name whose films have been absent from shelves, and whose legacy has unfortunately been overlooked: Léonce Perret.

Read my full review of Gaumont Treasures: 1897-1913 here at The L Magazine.

Husbands (1970)

Husbands is an essential companion piece to A Woman Under the Influence, made four years later. To see one without the other is to get only half of the story of domestic discontent pushed to its limits. Just as Gena Rowlands's Mabel of A Woman Under the Influence is frustrated and unfulfilled by her role as the stay-at-home mom who alternately waits for husband and kids to come home, the male trio at the core of Husbands are equally dissatisfied by the strict gender binary which has written out their role for them with little room for agency or expression. They are alienated from their wives and children, disconnected from their friends, and living only for "the job" and nothing else...

Husbands is an essential companion piece to A Woman Under the Influence, made four years later. To see one without the other is to get only half of the story of domestic discontent pushed to its limits. Just as Gena Rowlands's Mabel of A Woman Under the Influence is frustrated and unfulfilled by her role as the stay-at-home mom who alternately waits for husband and kids to come home, the male trio at the core of Husbands are equally dissatisfied by the strict gender binary which has written out their role for them with little room for agency or expression. They are alienated from their wives and children, disconnected from their friends, and living only for "the job" and nothing else...Read my full review of John Cassavetes' Husbands here at The L Magazine.

Woman on the Beach (2006)

What is remarkable about Hong’s directorial style is its directness. In this digital age, where the influence of technology over movies is so controversial, Hong seems to speak to a different sensibility. His style is sparse: that compositions seem natural seems to be the most important thing. What one notices in Woman on the Beach is a lack of stylized lighting, obvious color schemes, extreme high or low camera angles, fast cutting and special effects. Hong favors an unobtrusive camera, using long-takes to best capture the relaxed performances of his actors, with light zooming or panning in order to re-frame the action or pay particularly close attention to an actor...

What is remarkable about Hong’s directorial style is its directness. In this digital age, where the influence of technology over movies is so controversial, Hong seems to speak to a different sensibility. His style is sparse: that compositions seem natural seems to be the most important thing. What one notices in Woman on the Beach is a lack of stylized lighting, obvious color schemes, extreme high or low camera angles, fast cutting and special effects. Hong favors an unobtrusive camera, using long-takes to best capture the relaxed performances of his actors, with light zooming or panning in order to re-frame the action or pay particularly close attention to an actor...Read my full review of Hong Sang-Soo's Woman on the Beach here at Coupe Cinema.

Monday, August 17, 2009

Westward the Women (1951)

“Only two things in this world that scares me,” confesses Robert Taylor at the start of Westward the Women, “and a good woman is both of them!” As the veteran wagon guide Buck, he will have to confront both of his worst fears in a big way when he is hired by California territory settler Roy Whitman to lead 140 women from Chicago half-way across the country to his settlement, where a community of men are waiting eagerly for wives. This initial impetus for the story seemingly objectifies women to a social commodity — the men need wives to have children, and Whitman’s town relies on this cycle of life in order to prosper. But it is exactly this objectification that the narrative continually rejects and fights against throughout the movie. Much to Buck’s chagrin, his female “passengers” repeatedly transgress stringent gender binding, embracing this westward expansion as both a social and personal journey as well. For this band of women, Manifest Destiny is more than a geographical crusade — it’s about redefining oneself outside the strictures of society.

“Only two things in this world that scares me,” confesses Robert Taylor at the start of Westward the Women, “and a good woman is both of them!” As the veteran wagon guide Buck, he will have to confront both of his worst fears in a big way when he is hired by California territory settler Roy Whitman to lead 140 women from Chicago half-way across the country to his settlement, where a community of men are waiting eagerly for wives. This initial impetus for the story seemingly objectifies women to a social commodity — the men need wives to have children, and Whitman’s town relies on this cycle of life in order to prosper. But it is exactly this objectification that the narrative continually rejects and fights against throughout the movie. Much to Buck’s chagrin, his female “passengers” repeatedly transgress stringent gender binding, embracing this westward expansion as both a social and personal journey as well. For this band of women, Manifest Destiny is more than a geographical crusade — it’s about redefining oneself outside the strictures of society.Read my full review of Westward the Women here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

Arizona (1940)

“Put that money on the table or get ready to feel lead!” orders Phoebe Titus as she holds a shotgun on two lackeys who robbed her the night before. Although played by Jean Arthur (who was known for playing bold, independent female characters that could be both tough and romantic at the same time), this certainly isn’t the same actress we’re familiar with from Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, History Is Made at Night or Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Gone is the coiffed, good-humored sophisticate that was so endeared by audiences — that Jean Arthur has been replaced by one who’s face is covered in dirt and is clad in jeans, vest and cowboy hat (which is more in tune with Arthur’s performance as Calamity Jane four years earlier in The Plainsman). With the whole saloon at her knees, Phoebe gets her money back with the assistance of newly arrived Peter Muncie, but she could care less that he’s played by the soft-cheeked matinee idol-in-training William Holden. No — her eyes are on retribution and nothing else. “Timmons, take that whip and give Longstreet five of the best lashes you got in you,”she tells the crooks. “Longstreet, you do the same to him. And if either of you eases up, I’ll make it twenty.” Money in hand, Phoebe listens as the whip cracks off-screen. “Harder! That’s more like it.”

“Put that money on the table or get ready to feel lead!” orders Phoebe Titus as she holds a shotgun on two lackeys who robbed her the night before. Although played by Jean Arthur (who was known for playing bold, independent female characters that could be both tough and romantic at the same time), this certainly isn’t the same actress we’re familiar with from Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, History Is Made at Night or Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Gone is the coiffed, good-humored sophisticate that was so endeared by audiences — that Jean Arthur has been replaced by one who’s face is covered in dirt and is clad in jeans, vest and cowboy hat (which is more in tune with Arthur’s performance as Calamity Jane four years earlier in The Plainsman). With the whole saloon at her knees, Phoebe gets her money back with the assistance of newly arrived Peter Muncie, but she could care less that he’s played by the soft-cheeked matinee idol-in-training William Holden. No — her eyes are on retribution and nothing else. “Timmons, take that whip and give Longstreet five of the best lashes you got in you,”she tells the crooks. “Longstreet, you do the same to him. And if either of you eases up, I’ll make it twenty.” Money in hand, Phoebe listens as the whip cracks off-screen. “Harder! That’s more like it.”Read my full review of Arizona here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

The Gun Woman (1918)

When we first meet Texas Guinan in The Gun Woman – a character nameless except for the moniker “The Tigress” – she is outside of her saloon at night, lingering half in the shadows, lighting her cigarette. Pre-Dietrich and pre-Noir, Guinan has femme fatale written over every inch of her body — yet this was made in 1918, and it is a Western. The cinematic predecessors that influenced film noir (namely German Expressionist and American hardboiled literature, both of the 1920s) were years away from being developed. Yet there she is, a deadly, dangerous woman, lurking in the darkest corners of the Old West – our lady Tex, “The Gun Woman” herself.

Read my full review of The Gun Woman here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

49-17 (1917)

In the introduction to his essential and illuminating study The Silent Feminists: America’s First Women Directors, film historian Anthony Slide remarks that during the early days of cinema, “not only were women making films, but contemporary observers were making little of the fact. It was taken for granted that women might direct as often and as well as their male counterparts, and there was no reason to belabor this truth.” In the intervening decades, much of the legacy of women directors in the silent era has been lost or forgotten — films no longer exist and filmmakers’ lives and careers are ambiguous at best. How to reverse this process with so little evidence, and so few films? The release of Ruth Ann Baldwin’s 49-17 on DVD, her second feature film as director from 1917 – and the first known Western to be directed by a woman – was certainly a big step forward towards documenting this history and making it available to the public.

Read my full review of 49-17 here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

Women of the West

Contrary to how it is generally perceived, “The Western” is in no means an exclusively masculine genre. The West wasn’t founded solely by frontiersmen, cattle ranchers and John Ford, and cowboys weren’t the only ones with six-shooters hanging at their side, warming their bellies with whiskey, running the bad boys out of town on their horses, or corralling the livestock as part of a hard day’s work. Women were alongside them, and in some cases in front of them, every step of the way...

Co-written by Jenny Jediny and myself.

Rambo (2008)

The entries in the Rambo series, whether affectionately or derisively, are often referred to not by their original titles, but by the abbreviation “Rambo” plus whatever number film in the cycle they are referring to. Technically, this is only accurate for Rambo III. And while calling the fourth film simply Rambo might make this all the more confusing, the decision is ultimately quite significant. It heralds a new era for the Rambo franchise—a new generation of fans, a new film industry, a new cultural and political climate, and ultimately a new action hero. This is now sixteen years after the release of First Blood, and much more blood has been drawn since then, and many more wrongs committed. To stick by that original title would be to indicate that Rambo hasn’t moved beyond that initial film. But, as evinced by the other entries in the cycle, he clearly has, and throughout Rambo he will continue to change even more because, if anything, this latest film is all about movement, both as an aesthetic choice and narrative motif.

Read my full review of Rambo here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

Rambo III (1988)

Rambo III is a mess—an irreconcilable mélange of the awesome and the absurd, the ridiculous and the serious. Obstructing the narrative is a slew of contradictions and irregularities that break up what is otherwise a reworking of its predecessor, Rambo: First Blood Part II. But for something that tries to follow so closely the path set out by the previous two films, it is a surprisingly distinct entry in the series. I say “surprisingly” not because the other films are so cookie-cutter – in fact, if anything can be said for the Rambo cycle, it is that each entry has its own individual feel and conception of the titular character – but because Rambo emerges as a different entity seemingly against the intentions of filmmakers. Rambo III is an unwieldy beast that offers no easy, clear-cut analysis or summation, and for this the film is at once a headache and a delight, and ultimately an enigma.

Read my full review of Rambo III here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

The Ballad of Little Jo (1993)

At the very start of The Ballad of Little Jo, Josephine Monaghan finds herself caught in the dichotomous, reactionary web of nineteenth century American morality. Pregnant out of wedlock, her family takes possession of her child and sends her packing. On the road, a traveling salesman picks her up, seemingly engaging her as his assistant only to pawn her off to a couple of violent cowboys who chase her deep into the woods. Escaping, she flees to a local shop but finds hostility instead of sanctuary. Good girls would never get themselves in such a fix, it seems. When Josephine holds a pair of men’s trousers up in front of the mirror, the female shopkeeper warns, “Its against the law to dress improper to your sex.” Rejecting society’s label of “whore” because she wasn’t their idea of a “saint,” Josephine’s only recourse is the ultimate transgression: to cross the gender divide itself, from “Josephine” to “Jo.”

Read my full review of The Ballad of Little Jo here at Not Coming to a Theater Near You.

Dazzle (2009)

Watching Dazzle, I couldn’t help but thinking of the song “At the Window of Vulnerability.” Most of the (in)action occur by a window; not only does it look out over an Amsterdam street and a river, it also acts as a screen through which a young woman (Georgina Verbaan) projects her own anxiety and guilt. We never see her engage in the world around her, which seems to be one of her biggest problems. Throughout the film, she talks on the phone to a complete stranger (Rutger Hauer), retelling to him the various events she has seen through the window, such as a junkie masturbating in the street or a mouse that commits suicide by leaping into the river. She sees desperation, but is not moved to enact any change herself; contrarily, the open spectacle of need inflicts upon her a great guilt, which she feels is unwarranted. Unable to cope, she reaches out to the stranger on the phone, a doctor in Buenos Aires, who is confronting his own doubts about his profession and his life...

Read my full review of Dazzle here at The L Magazine.

FILM IST. a girl and a gun (2009)

In the grand tradition of epic poetry, FILM IST. a girl and a gun fuses found footage from cinema’s past and ancient Greek text, by the likes of Sappho, Hesiod and Plato, into 24 frames-per-second of kinetic ecstasy. Combing the vaults of international film archives and the Kinsey Institute, Austrian artist Gustav Deutsch returns to Tribeca with the third installment in his Film ist (“Film is…”) series, bringing to light some of the most entrancing and indelible images of early cinema that you’ve never seen. The spectacles range from purple-tinted bodybuilders to Annie Oakley, nudist athletes to stop-motion flowers that blossom before the camera’s eye, stag film models to gun-toting women. Using the Greek writings as intertitles, Deutsch orchestrates the images into a five-act structure: Genesis, Paradeisos, Eros, Thanatos and Symposion. Within this framework, seemingly disparate images collide, creating a new cinematic world of gods and goddesses...

Read my full review of FILM IST. a girl and a gun here at The L Magazine.

World Nomads: Haiti at The French Institute

It is only fitting that the French Institute would choose to open its World Nomads: Haiti film series with Jonathan Demme's The Agronomist (2004), a documentary about Jean Dominique, who (among other things) happened to found Haiti's first Cine Club at the French Institute in Port-au-Prince in 1961. Co-curated by Demme with filmmaker David Belle (founder of Ciné Institute, Haiti's film school) and the French Institute's Marie Losier, the series — along with its companion Haitian Documentary Series at The Maysels Institute — makes available a national cinema that has received far too little exposure, either in theaters or on DVD.

Read my full coverage of World Nomads: Haiti here at The L Magazine.

Departures (2008)

On the one hand, it's obvious why Departures won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. It's overflowing with a familiar cloyingness that won't alienate audiences, and yet there's ample "foreign-ness" to make it appealingly exotic. Recently laid-off Tokyo cellist Masahiro Motoki returns to his hometown with his wife (J-pop superstar Ryoko Hirosue) and secretly begins work as a mortician. Ashamed, he keeps it a secret from her — and, expectedly, she and the town find out and ostracize him.

But then there's the influence of Juzo Itami's uncouth, bodily humor, which exerts itself in Depatures through Motoki's boss, played by Tsutomu Yamazaki of Itami's Tampopo and The Funeral. Whether slobbering over fried chicken, making off-color jokes about rotting corpses or using Motoki as a "human model" for the ritualistic preparation of the body (which includes stuffing gauze in unwanted areas), Yamazaki brings a much-needed inappropriateness to the film. His zest for pervy unpretentiousness does not go unappreciated.

Originally published in The L Magazine.

The Outfit (1973)

Robert Duvall plays Parker (here called Macklin) with an understated hardboiled demeanor. No cracking wise here — Duvall understands that he is playing a businessman whose cool head and emotionless disconnect isn't a sign of sociopathy but of his integrity. After foiling a hitman's attempt on his life, Macklin discovers that an organization known as The Outfit is after him for knocking over one of their banks. No beating around the bush, he goes straight to the man responsible for placing the hit, Menner (Tim Carey, with his characteristic élan), robbing him of all his poker winnings and demanding $250,000 for the inconvenience of almost being killed.

Read my full review of The Outfit here at The L Magazine.

The Housemaid (1960)

Filming the story almost entirely in a cluttered, half-finished home, Kim Ki-young makes full use of narrow corridors and glass-paneled sliding doors to emphasize the sense of global paranoia that runs rampant throughout The Housemaid. Filming through chairs, banisters and windows, he turns the home into an inescapable prison of unrepressed passions. Once the skeletons come out of the closet with a vengeance in the film's second half, it is as though the outside world ceases to exist. This pulp-chamber drama reminds of something that Gil Brewer might have penned for that publisher of lurid poetics Gold Medal. In fact, both Brewer's 13 French Street (1951) and The Housemaid both share a common nightmare of corruption of the middle class home and the perversion of its moral system.

Read my full review of The Housemaid here at The L Magazine.

10 Rillington Place (1971)

If 10 Rillington Place weren't based on real events, it would take the warped mind of Jim Thompson to imagine such paranoid, psychosis-driven characters as the soft-spoken serial killer John Reginald Christie (Richard Attenborough) and his dim-witted, unknowing cohort Timothy John Evans (John Hurt). Christie is a closet deviant who lures desperate women to his home under false pretenses of being a doctor. The illiterate Evans moves his wife and child into the apartment above Christie because it's all he can afford. His life is nothing but two rooms the color of rotting mouse fur, filled with furniture his wife neglected to pay, and a child on the way that he can't afford. Unfortunate circumstances have thrown the group together, and while Christie's phony doctoring seemingly offers Evans and his wife a way out of this purgatorial existence, it's only the beginning of a descent into murder, madness, and the overbearing weight of guilt that's enough to bury any man alive and make them wish for the gallows...

Read my full review of 10 Rillington Place here at The L Magazine.

The GoodTimesKid (2005) and Mantrap (1926)

From Benten comes The GoodTimesKid (2005), the second feature from Azazel Jacobs (whose latest film, Momma's Man, was one of the best films of 2008, and is available on DVD from Kino). With the exception of a brief prologue, the film unfolds throughout the course of a single day as the unspoken ennui and anxiety of a trio of alienated misfits manifest themselves through spontaneous relationships and mad dashes for wild, illogical dreams...

Also, just out from Sunrise Silents is a never-before-available silent film, Mantrap (1926), starring that iconic flapper of the silver screen Clara Bow (who was only twenty-one at the time of the film's release). And while her role as the titular "It" girl from It (1927) certainly defined a bobbed-hair zeitgeist, it has also come to be the sole definer of her career (outside of the cartoon she inspired, Betty Boop). Mantrap's arrival on DVD is a welcome reminder of the flirtatious charm and uninhibited sexuality that were the key ingredients of Bow's comedic style...

Read my full review of The GoodTimesKid and Mantrap here at The L Magazine.

Tuesday, July 28, 2009

"Bardelys the Magnificent" (1926)

Bardelys the Magnificent (1926) marks Gilbert's fifth collaboration with director King Vidor, who also led Glibert to two of his greatest triumphs with The Big Parade (1925) and La Boheme (1926), breaking him out of the “pretty boy” mould and giving him challenging, meaty roles which brought his hitherto untapped acting potential. Vidor, similarly an unfortunately forgotten figure, was one of the top filmmakers of the 1920s, with a rarely equaled gift for naturalistic yet poetic storytelling, effortlessly moving between comedy, romance, drama and — as Bardelys the Magnificent proves — action, as well. A comic swashbuckler in the Douglas Fairbanks tradition (and one of the few that actually deserves the comparison and rivals any of the master's own films), Bardelys the Magnificent features Gilbert as a notorious ladykiller of the court, handing out lockets with snippets of his hair (which really come from a wig) like there's no tomorrow. When his abilities to win any woman are challenged, Gilbert masquerades as a wanted rebel in order to win the damsel’s hand. Unfortunately, he also wins the attention of the law, who want to hang him for his crimes against the king.

Read my full review of Bardelys the Magnificent here at The L Magazine.

"The John Barrymore Collection"

Considered one of the great actors — of both stage and screen — of his day, John Barrymore is the subject of an eponymous new box set from Kino, featuring four of the performer's silent pictures made between 1920 and 1928. Showing off his wide range of skills and charms, the set reminds us why the performer was once so beloved by audiences, and why he deserves to continue to be so. Despite his stage training and theatrical family background (he came from a long line of actors, and his siblings were the equally renowned Lionel and Ethel), John had a natural presence on screen. He may be best remembered for his screwball hamming in Twentieth Century (1934) opposite Carole Lombard, but he is anything but histrionic or over-the-top in these four films. His subtle but communicative control of bodily and facial gestures, debonair persona and iconic good looks make for a commanding screen presence.

Read my full review of The John Barrymore Collection here at The L Magazine.

"Last Year at Marienbad" (1961) and "Diary of a Suicide" (1972)

The attraction of the enigmatic has rarely been so strong as in a pair of French avant-garde films, one returning to DVD and one new to the format. Alain Resnais' Last Year at Marienbad (1961) and Stanislav Stanjoevic's Diary of a Suicide (1972) share not just two actors — the sphinx-like Delphine Seyrig and the inscrutable, deadpan Sacha Pitoeff — but also a common romanticized ideal regarding the mystery of narrative. The central action of both films is, essentially, one character telling a story to another, though this hardly does justice to either of the films' richly nuanced scripts or the entrancing performances of the actors. Both films feed off our desire for resolution and clarity, and in denying — or drawing out — our needs, they become commentaries on listening and perception as much as storytelling.

Read my reviews of Last Year at Marienbad and Diary of a Suicide here at The L Magazine.

Au Bonheur Des Dames (1930)

Concurrently a modernist fantasia and urban nightmare, Au Bonheur Des Dames focuses on the rivalry between a fast-rising department store, Ladies' Paradise, and a small mom-and-pop storefront across the street. A 20-year-old Dita Parlo (that vision of monochromatic beauty from Vigo's L'Atalante and Renoir's Grand Illusion) stars as the young woman caught between the two businesses. Arriving in Paris to work in her uncle's small fabric shop, Parlo finds the sky literally raining advertisements — planes overhead are dropping flyers for Ladies' Paradise. In an urban montage that rivals the surreal multiple-exposures of Murnau's Sunrise and Walter Ruttmann's Berlin: Symphony of a Big City, Parlo is accosted by visual representations of the clamor and crowds of the metropolis, a sequence which culminates in the excessive splendor of Ladies' Paradise, a department store to end department stores. A palace of fast-moving crowds, shiny objects, grand staircases and sickeningly ornate architecture, the department store is a beastly manifestation of all of consumerism's grand promises.

Read my full review of Au Bonheur Des Dames here at The L Magazine.

Shinobi no Mono 4: Siege (1964)

The fourth in a series of eight films chronicling the role of the ninja in Japan's turbulent feudal past, Shinobi no Mono 4: Siege (1964) opens at the dawn of the Tokugawa Period, as a peace treaty between the reigning Shogun and his rival clan, the Toyotomi, is signed. The treaty, however, is just the calm before the storm, as the Toyotomi get word of the Tokugawa's secret plotting to destroy them once and for all. Coming to their rescue is legendary ninja Kirigakure (series star Raizo Ichikawa, who made nearly 100 films in his fourteen-year career, cut short by his death at the age of 38), but when he is kidnapped in a cunning ambush by enemy ninjas, even he must wonder if defeat is inevitable.

Read my full review or Shinobi no Mono 4: Siege here at The L Magazine.

"Man Hunt" (1941)

Known mostly for his Weimar-era silent films, Fritz Lang's career as an exile in Hollywood is all too often overlooked not only by audiences, but also by home video distributors. His 1927 sci-fi epic Metropolis (1927) may get all the buzz, but it's hard to deny that it is heavily marred by wife Thea von Harbou's cloying and sentimental script. Far better are Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler (1922) and M (1931), neither of which have lost any of their edginess or grit after over seven decades, and both of which are available on nicely restored DVDs by Kino and Criterion, respectively. Slowly but surely, his near-forgotten American films, many of which are either on par or superior to his work in Germany, are making their way to DVD. Just released today is his near-forgotten Man Hunt (1941), an anti-Nazi thriller whose masterfully and subtly crafted suspense rises above any mere label of propaganda.

Read my full review of Man Hunt here at The L Magazine.

"Falling Down" (1993)

"The street was mine," P.I. Mike Hammer lamented in Mickey Spillane's One Lonely Night back in 1952, acknowledging a loss of security and identity as The City mutated out-of-control into a messy, violent, overpopulated asphalt jungle. Forty-one years later, the phrase echoed loudly throughout Joel Schumacher's nightmare of urban discontent, Falling Down (1993), which is being rereleased today in both a Deluxe Edition DVD and Blu-Ray. Time has only shown how bold and audacious Schumacher's film was, from its claustrophobic opening highway scene borrowed from Fellini's 8 1/2 to a high-noon showdown on a Venice Beach pier that recalls the hardboiled romanticism of Jean-Pierre Melville. And then there's the matter of its anachronistic central character, a noir protagonist straight out of the 1950s who defies notions of hero and antihero, victim and villain. Out of work, prevented from seeing his daughter on her birthday by a restraining order, and stuck a traffic jam on a sweltering summer morning — Michael Douglas just snaps. Abandoning his car, he crosses Los Angeles on foot, exacting vengeance for all of society's hypocrisy and corruption.

Read my full review of Falling Down here at The L Magazine.